Retrospectives are the last thing a team does during a Sprint. There are a wide variety of approaches and formats one can use for Retrospectives, but the one thing all have in common is that the Retrospective must produce tangible results. One extremely effective way I have found to help ensure that the Retrospective meets this vital goal is to build a Team Improvement Backlog using the items the team identifies as action items.

A Team Improvement Backlog is nothing more than a prioritized list of action items the team comes up with during its Retrospectives. The most common recommendation, and one I heartily endorse, is that the team collectively chooses the top one or two items on the Team Improvement Backlog at or near the end of each Retrospective and then decides how to implement them and how to demonstrate success. Just like user stories, Team Improvement Backlog items need to have acceptance criteria -- the all-important definition of done.

There are a couple of nuances that can play into management of the Team Improvement Backlog. In general, items teams add to their improvement backlogs are public in keeping with the agile and Scrum values of openness and transparency. There are occasions, however, when I have recommended that certain items be kept private to the team. Examples include specific team interaction items, particularly when those items address individual behaviors. Retrospectives are sometimes more like the closed locker room meetings sports teams hold when they are experiencing a crisis. Teams typically do not allow reporters or even coaches into the locker room during such meetings simply because what the team members have to say to each other is strictly for their benefit as a team. In my coaching experience, private improvement backlog items are rare, but it's a handy tool to have in your bag especially when teams are storming.

Keep the Team Improvement Backlog visible in the team room and track progress at each Retrospective at the latest. Individuals who take on improvement items should also be talking about their work and plans during the Daily Scrum.

If you're not already using a Team Improvement Backlog, add this handy tool to your repertoire and use it to help your teams grow.

All for now....

...-.-

Friday, December 10, 2010

Wednesday, December 8, 2010

ScrumMaster Dilemmas

A few weeks ago, during a Product Owner class I was teaching, the lone practicing ScrumMaster in the room raised his hand after I had finished the section of the course reviewing Scrum roles. His question was basically this: "So, you just said one of the ScrumMaster's functions is to be a bulldozer, but when I solved a problem for my team last week, they accused me of 'throwing them under the bus' and now they won't talk about impediments anymore. What am I supposed to do?"

After learning more about the situation, I understood what had happened. At the last Retrospective, the team had raised an issue they were having with their Product Owner and, seeing himself as the fullback, snowplow, bulldozer, problem-solver, the ScrumMaster had simply taken the team's concerns to the Product Owner and worked out a solution. When he (the ScrumMaster) reported back to the team during a Daily Scrum his progress in resolving the issue with the Product Owner, the team reacted very negatively, as the ScrumMaster had described in his original question.

His confusion and genuine sense of hurt were palpable. He thought his role was to clear the road for the team so that they could get their work done as efficiently and effectively as possible. His point is entirely valid, but his experience demonstrates one of the many dilemmas that face ScrumMasters.

Take it to the team!

In her excellent book*, Lyssa Adkins gives this advice again and again. Self-organizing teams need to be empowered to solve their own problems -- or at least to devise prospective solutions to the problems they face. The ScrumMaster in my class did not realize that self-organizing teams, even those that have only been practicing for a few months, do not want to be presented with solutions to problems. Instead, as Lyssa points out, self-organizing teams want, and need, to be presented with problems. The team is then empowered to devise solutions -- and the team's solution will be the best one for that team. It may not be the solution the ScrumMaster would have chosen, but that does not change this essential fact.

Despite the best of intentions, ScrumMasters run into difficulties with their teams when they take on problems and solve them without team involvement. The team may ask their ScrumMaster to implement the solution to a problem, but the team itself needs to solve the problem. Many ScrumMasters came from backgrounds where individual problem solving was a major part of their job descriptions. Perhaps they were even evaluated on the basis of their individual problem-solving prowess. In a Scrum (or other agile framework) team environment, the equation changes. Problem solving abilities are still valuable, but within the context of of the self-organizing team.

ScrumMasters must engage in a delicate balancing act, being the bulldozer, fullback, or snowplow for their team, yet not imposing solutions on the team. It is more difficult to achieve this balance when a ScrumMaster is responsible for more than one team. Under pressure to help their teams succeed and with a severely limited amount of time and attention to offer to each team, such ScrumMasters are naturally inclined to gather lists of problems and run with them, handing solutions to their teams in rapid succession. This situation is bad for the teams, stunting their growth and inviting resentment against their ScrumMaster; it is also bad for the ScrumMaster who never really has time to get to know each team and the various individuals at the depth necessary to achieve the highest degree of effectiveness.

So what's a ScrumMaster to do? "Take it to the team," let the team solve problems, and keep the wolves at bay.

All for now....

...-.-

*Lyssa Adkins, Coaching Agile Teams: A Companion for ScrumMasters, Agile Coaches, and Project Managers in Transition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Addison-Wesley, 2010.

After learning more about the situation, I understood what had happened. At the last Retrospective, the team had raised an issue they were having with their Product Owner and, seeing himself as the fullback, snowplow, bulldozer, problem-solver, the ScrumMaster had simply taken the team's concerns to the Product Owner and worked out a solution. When he (the ScrumMaster) reported back to the team during a Daily Scrum his progress in resolving the issue with the Product Owner, the team reacted very negatively, as the ScrumMaster had described in his original question.

His confusion and genuine sense of hurt were palpable. He thought his role was to clear the road for the team so that they could get their work done as efficiently and effectively as possible. His point is entirely valid, but his experience demonstrates one of the many dilemmas that face ScrumMasters.

Take it to the team!

In her excellent book*, Lyssa Adkins gives this advice again and again. Self-organizing teams need to be empowered to solve their own problems -- or at least to devise prospective solutions to the problems they face. The ScrumMaster in my class did not realize that self-organizing teams, even those that have only been practicing for a few months, do not want to be presented with solutions to problems. Instead, as Lyssa points out, self-organizing teams want, and need, to be presented with problems. The team is then empowered to devise solutions -- and the team's solution will be the best one for that team. It may not be the solution the ScrumMaster would have chosen, but that does not change this essential fact.

Despite the best of intentions, ScrumMasters run into difficulties with their teams when they take on problems and solve them without team involvement. The team may ask their ScrumMaster to implement the solution to a problem, but the team itself needs to solve the problem. Many ScrumMasters came from backgrounds where individual problem solving was a major part of their job descriptions. Perhaps they were even evaluated on the basis of their individual problem-solving prowess. In a Scrum (or other agile framework) team environment, the equation changes. Problem solving abilities are still valuable, but within the context of of the self-organizing team.

ScrumMasters must engage in a delicate balancing act, being the bulldozer, fullback, or snowplow for their team, yet not imposing solutions on the team. It is more difficult to achieve this balance when a ScrumMaster is responsible for more than one team. Under pressure to help their teams succeed and with a severely limited amount of time and attention to offer to each team, such ScrumMasters are naturally inclined to gather lists of problems and run with them, handing solutions to their teams in rapid succession. This situation is bad for the teams, stunting their growth and inviting resentment against their ScrumMaster; it is also bad for the ScrumMaster who never really has time to get to know each team and the various individuals at the depth necessary to achieve the highest degree of effectiveness.

So what's a ScrumMaster to do? "Take it to the team," let the team solve problems, and keep the wolves at bay.

All for now....

...-.-

*Lyssa Adkins, Coaching Agile Teams: A Companion for ScrumMasters, Agile Coaches, and Project Managers in Transition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Addison-Wesley, 2010.

Monday, October 25, 2010

Scrum is more than just iterative and incremental

People often talk about Scrum as if it were nothing more than an iterative, incremental development process. Taking just these two aspects of Scrum makes it seem like it would be easy just to bolt Scrum onto existing development practices and organizational structures. I have trained and coached and talked -- either in person or on discussion lists -- with people who were completely comfortable calling their functionally delimited, mini-waterfall processes "Scrum" or "Agile."

"Well, we deliver a release every month that builds on previous month's release," is a common refrain.

A few quick questions reveal what's actually going on:

"Great! How's your quality? Is it getting better with each release? Are your teams getting better? Does every release contain the most valuable features you could possibly deliver?"

"Um, well...." is the usual response when an organization has adopted the superficial qualities of Scrum while ignoring the deeper principles and the practices they inform.

Iterative and incremental development are two results of Scrum done well, not the essence of Scrum. So what, you ask, is the essence of Scrum? I believe Scrum is about building cross-functional teams that are capable of learning how to do better work every day. Focusing on working software as the primary measure of progress by making use of the Sprint and daily planning cycles and the Sprint Review (to show our work) provides the framework for technical innovation -- and more basically, getting the job done, which is a huge challenge by itself in most organizations. The Retrospective gives teams the mechanism to improve both their degree of teamwork and, to a greater or lesser extent, the organizational environment in which they work. Learning teams, when propagated and nurtured, produce learning organizations that have a built-in competitive advantage over their less dynamic competitors.

Scrum is also about letting go of false measures, unrealistic planning, and failed control mechanisms. Measuring team throughput (Velocity) rather individual utilization provides a realistic tool for planning. The planning itself changes from activity and milestone-based to feature- and value-based, using teams' demonstrated ability to deliver working software as the key metric. Having teams pull work from the top of a prioritized Product Backlog ensures that, by definition, the highest-priority features are being worked on at all times and that each release contains the highest-priority, and therefore most valuable, features that could be delivered. Finally, allowing teams to deliver features, instead of relying the thoroughly discredited industrial practice of externally assigned individual tasks, opens the door to creative solutions -- and breakthrough productivity.

Where does quality fit into all of this? Returning again to the agile principle of working software as the primary measure of progress, non-working, buggy, software cannot demonstrate progress and therefore cannot be called "done." Teams and organizations that hold true to this principle have the capacity to do truly amazing things in an industry too often characterized by the poor quality of its products.

This is by no means a comprehensive list, but for me, right now, these are the key features of Scrum.

All for now....

...-.-

"Well, we deliver a release every month that builds on previous month's release," is a common refrain.

A few quick questions reveal what's actually going on:

"Great! How's your quality? Is it getting better with each release? Are your teams getting better? Does every release contain the most valuable features you could possibly deliver?"

"Um, well...." is the usual response when an organization has adopted the superficial qualities of Scrum while ignoring the deeper principles and the practices they inform.

Iterative and incremental development are two results of Scrum done well, not the essence of Scrum. So what, you ask, is the essence of Scrum? I believe Scrum is about building cross-functional teams that are capable of learning how to do better work every day. Focusing on working software as the primary measure of progress by making use of the Sprint and daily planning cycles and the Sprint Review (to show our work) provides the framework for technical innovation -- and more basically, getting the job done, which is a huge challenge by itself in most organizations. The Retrospective gives teams the mechanism to improve both their degree of teamwork and, to a greater or lesser extent, the organizational environment in which they work. Learning teams, when propagated and nurtured, produce learning organizations that have a built-in competitive advantage over their less dynamic competitors.

Scrum is also about letting go of false measures, unrealistic planning, and failed control mechanisms. Measuring team throughput (Velocity) rather individual utilization provides a realistic tool for planning. The planning itself changes from activity and milestone-based to feature- and value-based, using teams' demonstrated ability to deliver working software as the key metric. Having teams pull work from the top of a prioritized Product Backlog ensures that, by definition, the highest-priority features are being worked on at all times and that each release contains the highest-priority, and therefore most valuable, features that could be delivered. Finally, allowing teams to deliver features, instead of relying the thoroughly discredited industrial practice of externally assigned individual tasks, opens the door to creative solutions -- and breakthrough productivity.

Where does quality fit into all of this? Returning again to the agile principle of working software as the primary measure of progress, non-working, buggy, software cannot demonstrate progress and therefore cannot be called "done." Teams and organizations that hold true to this principle have the capacity to do truly amazing things in an industry too often characterized by the poor quality of its products.

This is by no means a comprehensive list, but for me, right now, these are the key features of Scrum.

All for now....

...-.-

Tuesday, September 28, 2010

WFH Scrum

Working From Home (WFH) is an amazing thing. I have done it for years, off and on, and I really like it. Studies have repeatedly shown that people are more motivated, more focused, and more productive when working from home than when working at the office. Another major benefit is for people who face long daily commutes. Not only do they not have to spend two or more hours of utterly unproductive time driving to and from the office, people working from home also reduce traffic volume and air pollution, both major concerns where I live on the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains of Colorado.

But how does one accommodate WFH within a Scrum team? I have coached a few teams that wrestled with this issue. It is tempting to say "everyone needs to be here, every day." And indeed, that is the only way to ensure the highest-possible bandwidth communication within a team. Given my own affinity for WFH, however, I decided the dogmatic approach would be neither effective nor realistic.

The approach I have adopted consistently -- and successfully -- is to work with the team to make sure everyone understands the importance of the principle of face-to-face communication and then recommend a few WFH ground rules for the team's consideration:

Let me know if you find these suggestions reasonable, useful -- or not.

All for now....

...-.-

But how does one accommodate WFH within a Scrum team? I have coached a few teams that wrestled with this issue. It is tempting to say "everyone needs to be here, every day." And indeed, that is the only way to ensure the highest-possible bandwidth communication within a team. Given my own affinity for WFH, however, I decided the dogmatic approach would be neither effective nor realistic.

The approach I have adopted consistently -- and successfully -- is to work with the team to make sure everyone understands the importance of the principle of face-to-face communication and then recommend a few WFH ground rules for the team's consideration:

- During the first Sprint or two, everyone needs to be physically present while we learn how to apply the rules of Scrum in practice

- When the team decides it is ready to run a WFH experiment, I suggest the following ground rules:

- Everyone is present for Sprint Planning, Story Time, Sprint Review, and Retrospective, which generally works out to be three days in each two-week Sprint

- Use Skype or other video conferencing technology to facilitate the Daily Scrum -- voice-only dial-in may suffice temporarily, but is not adequate over the long-term

- The team needs to adopt a standard, high-bandwidth communication medium/technology, such as Skype with video, that all team members commit to use for daily collaboration

- The Daily Scrum rules: if team members decide pairing or other face-to-face contact is needed, the necessary team members must be physically present even if it means driving to the office after the Daily Scrum, although we try to avoid the latter whenever possible

- Try to give people as much predictability as possible, but the team's needs trump all else

Let me know if you find these suggestions reasonable, useful -- or not.

All for now....

...-.-

Friday, September 10, 2010

Rehumanize Your Work

I was -- and remain -- a big fan of the popular music that characterized the 1980s. One of my favorite bands was The Police and one of my favorite songs was "Rehumanize Yourself" from their album Ghost in the Machine. That song was never a radio-play hit, but it always hit home with me. Listening to that album the other day on my iPod reminded me why it is exactly that I now spend my working life at what is essentially Agile evangelism.

Many of the key reasons companies decide to adopt Agile are based on hard-nosed financial, business, value, and competitiveness calculations. And that is as it should be. After all, without a competitive business there would be no employment. So yes, the competitive boost companies derive from Agile is a key benefit. But for me, the greatest benefit is the rehumanization of work and of the workplace.

Among the most insidious results of Frederick Winslow Taylor's Scientific Management was the utter and complete de-humanization of work and the workplace. In the software development world, the various pre-packaged methodologies that have come along have all contained the spirit of Taylorism with its cynical, command-and-control approach to the people doing the work.

The real genius of the Toyota Production System, to me, was its inventors' realization that the assembly line was not mechanistic; it was, in fact, a social system that could only work properly if it took into account the human element. The result was the andon cord, which gave all workers on the floor both the responsibility and the authority to control their work.

Henry Ford once said: "Why is it that when I want to hire a pair of hands, a brain comes attached to them?" This is the essence of Taylorism -- and the antipathy of the entire concept of the andon cord. No worker in any of Henry Ford's factories was ever given authority to stop the line.

Software development -- or any other type of product development -- obviously requires hands that are attached to a brain, but traditional methodologies assume that the brain thus involved must be allowed to work only within rigid constraints because the people doing the work obviously have neither the capacity nor the inclination to take responsibility for their work. This, too, is the essence of Taylorism.

The genius of XP and Scrum, which are my main focus within Agile, is the recognition of the human element, of the fact that product development is primarily a social activity. By offering the people doing the work the authority to accomplish that work as they see fit, by giving them the responsibility to ensure that the work is done in the best possible way, and by establishing the social environment in which that authority and responsibility can be expressed to its fullest, Scrum and XP provide the best known framework for rehumanizing the work and workplace.

Along with the values, principles, and practices of XP and Scrum, conscientious, dedicated leadership completes the puzzle. So how about it? What will you do, today, to rehumanize your work?

All for now...

...-.-

Many of the key reasons companies decide to adopt Agile are based on hard-nosed financial, business, value, and competitiveness calculations. And that is as it should be. After all, without a competitive business there would be no employment. So yes, the competitive boost companies derive from Agile is a key benefit. But for me, the greatest benefit is the rehumanization of work and of the workplace.

Among the most insidious results of Frederick Winslow Taylor's Scientific Management was the utter and complete de-humanization of work and the workplace. In the software development world, the various pre-packaged methodologies that have come along have all contained the spirit of Taylorism with its cynical, command-and-control approach to the people doing the work.

The real genius of the Toyota Production System, to me, was its inventors' realization that the assembly line was not mechanistic; it was, in fact, a social system that could only work properly if it took into account the human element. The result was the andon cord, which gave all workers on the floor both the responsibility and the authority to control their work.

Henry Ford once said: "Why is it that when I want to hire a pair of hands, a brain comes attached to them?" This is the essence of Taylorism -- and the antipathy of the entire concept of the andon cord. No worker in any of Henry Ford's factories was ever given authority to stop the line.

Software development -- or any other type of product development -- obviously requires hands that are attached to a brain, but traditional methodologies assume that the brain thus involved must be allowed to work only within rigid constraints because the people doing the work obviously have neither the capacity nor the inclination to take responsibility for their work. This, too, is the essence of Taylorism.

The genius of XP and Scrum, which are my main focus within Agile, is the recognition of the human element, of the fact that product development is primarily a social activity. By offering the people doing the work the authority to accomplish that work as they see fit, by giving them the responsibility to ensure that the work is done in the best possible way, and by establishing the social environment in which that authority and responsibility can be expressed to its fullest, Scrum and XP provide the best known framework for rehumanizing the work and workplace.

Along with the values, principles, and practices of XP and Scrum, conscientious, dedicated leadership completes the puzzle. So how about it? What will you do, today, to rehumanize your work?

All for now...

...-.-

Tuesday, August 24, 2010

It's all about the Raspberry Jam

“The Law of Raspberry Jam: the wider any culture is spread, the thinner it gets.” -- Alvin Toffler

I recently delivered a series of Product Owner training courses for a large (massive, really) multinational corporation. The company has an Agile rollout strategy and a reasonable amount of tactical planning in place for making it happen. During the course of the training, one of the more interesting discussions that arose revolved around how many teams each Product Owner would serve. The Scrum answer is, of course, one and only one Product Owner per Scrum team. There are a variety of reasons for this one-to-one relationship between Product Owner and team, a few of which are:

Toffler was talking about cultures, but the same is true of people and roles. Spreading a Product Owner over multiple teams inevitably thins that Product Owner's commitment to each team. The thinning of commitment makes the building of trust and mutual respect much more difficult, perhaps rendering that vital connection impossible.

Then there is the issue of keeping the backlog prioritized, groomed, and ready for each team to pull the highest-priority stories into each Sprint. I worked with a team a few months ago (at a different client) that had outrun its Product Owner's ability to keep the backlog stocked with appropriate stories. As that team's velocity increased, the Product Owner simply could not keep up. Imagine that situation multiplied by five!

The one-Product-Owner-for-five-teams experiment has not gotten off the ground yet, but I am very interested to see how it goes. As I told the trainees, it might work. But then again, there was no data or other evidence to support that supposition out of the gate, whereas for the standard format of one Product Owner per team, there is a huge amount of data that demonstrate success.

All for now...

...-.-

I recently delivered a series of Product Owner training courses for a large (massive, really) multinational corporation. The company has an Agile rollout strategy and a reasonable amount of tactical planning in place for making it happen. During the course of the training, one of the more interesting discussions that arose revolved around how many teams each Product Owner would serve. The Scrum answer is, of course, one and only one Product Owner per Scrum team. There are a variety of reasons for this one-to-one relationship between Product Owner and team, a few of which are:

- The Product Owner is a pig, a committed member of the team who shares in the ups and downs of the team's experience

- The Product Owner is the sole voice of the customer, the single source of business information on the team

- The Product Owner continuously prioritizes the Product Backlog, ensuring that the team always pulls the highest-priority work into each Sprint

- The Product Owner makes sure that the team never runs out of high-priority stories to work on

- The Product Owner and team build a relationship of trust and mutual respect based on shared work toward a common goal

Toffler was talking about cultures, but the same is true of people and roles. Spreading a Product Owner over multiple teams inevitably thins that Product Owner's commitment to each team. The thinning of commitment makes the building of trust and mutual respect much more difficult, perhaps rendering that vital connection impossible.

Then there is the issue of keeping the backlog prioritized, groomed, and ready for each team to pull the highest-priority stories into each Sprint. I worked with a team a few months ago (at a different client) that had outrun its Product Owner's ability to keep the backlog stocked with appropriate stories. As that team's velocity increased, the Product Owner simply could not keep up. Imagine that situation multiplied by five!

The one-Product-Owner-for-five-teams experiment has not gotten off the ground yet, but I am very interested to see how it goes. As I told the trainees, it might work. But then again, there was no data or other evidence to support that supposition out of the gate, whereas for the standard format of one Product Owner per team, there is a huge amount of data that demonstrate success.

All for now...

...-.-

Thursday, May 13, 2010

When do we start? When should we finish?

The snow that fell yesterday -- yes snow, yes on May 12 -- along the northern Front Range of Colorado has just about melted and it looks like spring again, even though it doesn't necessarily feel that way when one steps outside. The mountains give the appearance of mid-winter, which is encouraging given the lower-than-average snow pack to date.

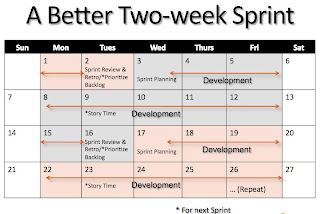

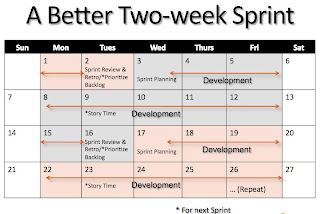

In any case, the questions that form the title of this post are among the most frequently asked when I am both training and coaching. The context is Sprint begin-end boundaries and the answers I give are consistent. I encourage organizations and teams to follow the Lean principle of building-in quality, that is, make everything as unlikely to break as possible. When it comes to Sprint boundaries, regardless of the length of the Sprints, the least likely candidates are starting on Mondays and ending on Fridays.

There are several reasons why Monday-Friday Sprint boundaries are suboptimal. In the USA at least, most holidays fall on Mondays, almost certainly assuring disruption of Sprint planning at least a few times every year. And while ending Sprints on Fridays might seem to offer the prospect of a nice break in between Sprints, the all-too-common refrain from the team at the Sprint Review is: "Oh yeah, we're done with everything, but we just have a little testing/coding/cleanup, etc., to finish over the weekend." Uh-oh.

Fortunately, there is an extremely simple method of fixing these (and many other) common problems resulting from Monday-Friday Sprint boundaries: start and finish in the middle of the week. I personally like starting fresh with Sprint Planning on Wednesday mornings and wrapping up with the Sprint Review and Retrospective on Tuesday afternoons. Using this Sprint boundary template immediately remedies the Monday-holiday disruption. Finishing the Sprint on Tuesday afternoon -- with the Retrospective as the last thing the team does, always, without fail -- very neatly eliminates "we're done, but we'll finish over the weekend" syndrome as well. This one element, finishing work, is worthy of another blog post all to itself.

Another benefit of the Wednesday-Tuesday Sprint cycle is that it supports adherence to an oft-violated Agile principle: sustainable pace. As a coach, I am not about to encourage or even allow teams to get into the habit of working weekends between Sprints. The most effective way I have discovered to deal with this problem is simply to make it impossible: there is no weekend or other exploitable time between Sprints.

Closing out each Sprint on Tuesday with the Retrospective provides the team with the full experience of accomplishment and closure, of finishing the work of one Sprint before moving on to the next. Indeed, I invariably find that teams are anxious to get started on the next Sprint and welcome the opportunity to start fresh the very next morning. An added benefit is that holding Sprint celebrations on Tuesdays often results in a smaller tab at the team's favorite restaurant or bar, which often offer discounts to encourage mid-week trade.

Think about it and let me know about your experience with Sprint boundaries.

All for now....

...-.-

In any case, the questions that form the title of this post are among the most frequently asked when I am both training and coaching. The context is Sprint begin-end boundaries and the answers I give are consistent. I encourage organizations and teams to follow the Lean principle of building-in quality, that is, make everything as unlikely to break as possible. When it comes to Sprint boundaries, regardless of the length of the Sprints, the least likely candidates are starting on Mondays and ending on Fridays.

There are several reasons why Monday-Friday Sprint boundaries are suboptimal. In the USA at least, most holidays fall on Mondays, almost certainly assuring disruption of Sprint planning at least a few times every year. And while ending Sprints on Fridays might seem to offer the prospect of a nice break in between Sprints, the all-too-common refrain from the team at the Sprint Review is: "Oh yeah, we're done with everything, but we just have a little testing/coding/cleanup, etc., to finish over the weekend." Uh-oh.

Fortunately, there is an extremely simple method of fixing these (and many other) common problems resulting from Monday-Friday Sprint boundaries: start and finish in the middle of the week. I personally like starting fresh with Sprint Planning on Wednesday mornings and wrapping up with the Sprint Review and Retrospective on Tuesday afternoons. Using this Sprint boundary template immediately remedies the Monday-holiday disruption. Finishing the Sprint on Tuesday afternoon -- with the Retrospective as the last thing the team does, always, without fail -- very neatly eliminates "we're done, but we'll finish over the weekend" syndrome as well. This one element, finishing work, is worthy of another blog post all to itself.

Another benefit of the Wednesday-Tuesday Sprint cycle is that it supports adherence to an oft-violated Agile principle: sustainable pace. As a coach, I am not about to encourage or even allow teams to get into the habit of working weekends between Sprints. The most effective way I have discovered to deal with this problem is simply to make it impossible: there is no weekend or other exploitable time between Sprints.

Closing out each Sprint on Tuesday with the Retrospective provides the team with the full experience of accomplishment and closure, of finishing the work of one Sprint before moving on to the next. Indeed, I invariably find that teams are anxious to get started on the next Sprint and welcome the opportunity to start fresh the very next morning. An added benefit is that holding Sprint celebrations on Tuesdays often results in a smaller tab at the team's favorite restaurant or bar, which often offer discounts to encourage mid-week trade.

Think about it and let me know about your experience with Sprint boundaries.

All for now....

...-.-

Wednesday, April 7, 2010

Confessions of an Agile Purist

It's sunny down in Texas today and the late, great Stevie Ray Vaughan is cranking from my Mac's tiny speakers. It all seems appropriate somehow, Texas blues and the recent accusation that I am an "Agile Purist." My initial thought was that that label was somehow derogatory, a slap in the face, a put-down. A few sweet licks from SRV's guitar has helped me see the light, however. Now I'm ready to embrace the Agile Purist tag rather than trying to wash it off.

So here's the deal, I train and coach Agile teams and have been extremely successful at both of these related endeavors. My philosophy is a simple one: present the rules of the product development game, primarily Scrum, but drawing also on the best that XP has to offer, with a little Lean thrown in for leavening, so that my trainees both know the rules of the game and have the beginnings of a sense of how to take the field and begin to play. Experienced Agilists know all too well that the framework is very simple and lightweight, but that does not make it easy to put into practice. Indeed, simple most certainly does not equate to easy in this context. So my guiding principle is to make sure that everyone in my training classes emerges knowing what to do when they hit the ground, whether with me there to coach them or not.

When I'm coaching, I follow the same principle. Everyone knows exactly what to do -- or at least what to expect -- every single day that I'm on the ground with a client, whether it's an ordinary day with a daily Scrum, a Sprint planning day, or a Review/Demo and Retrospective day. What happens, specifically, during each day is highly variable and hence where the difficulty lies in putting this simple framework into practice. Starting with that Agile Purist approach, which in reality means making sure that everyone knows what to do/expect coming into each day on the job, has served my clients very, very well indeed.

What this means is that I train and coach client teams to play by the rules so that they have confidence in what they are doing and in their individual and collective ability to do it from day one. I want them to learn good habits so that when the unexpected happens -- or when the entirely predictable challenges arise -- they are in the best possible position to make adjustments and continue moving forward with their Agile practice.

Aside from the purely practical, experiential basis for following the rules of the game, there is this one other thing that informs my work as a trainer and coach: I actually believe in the value of the core Agile principles captured in the Agile Manifesto. I believe that putting those principles into practice -- playing by the rules -- has a proven record of success, not just in getting the right product to market, at the right time, and for the right price, but that those principles translated into practices create a healthy, productive, and adaptive work environment that none of the prepackaged methodologies can ever hope to touch.

My devotion to Agile principles and practices, those rules of the game, is therefore not based on a pedantic need to follow some arbitrary formula. Once a team I am coaching learns how to play at a basic level, which typically happens very quickly, I help them learn how to adapt their practices as needed, all the while keeping the principles in the forefront of everyone's mind. We're just not going to start there, on the highly adaptive end of the time line.

So yes, I admit it: I am an Agile Purist.

All for now....

...-.-

So here's the deal, I train and coach Agile teams and have been extremely successful at both of these related endeavors. My philosophy is a simple one: present the rules of the product development game, primarily Scrum, but drawing also on the best that XP has to offer, with a little Lean thrown in for leavening, so that my trainees both know the rules of the game and have the beginnings of a sense of how to take the field and begin to play. Experienced Agilists know all too well that the framework is very simple and lightweight, but that does not make it easy to put into practice. Indeed, simple most certainly does not equate to easy in this context. So my guiding principle is to make sure that everyone in my training classes emerges knowing what to do when they hit the ground, whether with me there to coach them or not.

When I'm coaching, I follow the same principle. Everyone knows exactly what to do -- or at least what to expect -- every single day that I'm on the ground with a client, whether it's an ordinary day with a daily Scrum, a Sprint planning day, or a Review/Demo and Retrospective day. What happens, specifically, during each day is highly variable and hence where the difficulty lies in putting this simple framework into practice. Starting with that Agile Purist approach, which in reality means making sure that everyone knows what to do/expect coming into each day on the job, has served my clients very, very well indeed.

What this means is that I train and coach client teams to play by the rules so that they have confidence in what they are doing and in their individual and collective ability to do it from day one. I want them to learn good habits so that when the unexpected happens -- or when the entirely predictable challenges arise -- they are in the best possible position to make adjustments and continue moving forward with their Agile practice.

Aside from the purely practical, experiential basis for following the rules of the game, there is this one other thing that informs my work as a trainer and coach: I actually believe in the value of the core Agile principles captured in the Agile Manifesto. I believe that putting those principles into practice -- playing by the rules -- has a proven record of success, not just in getting the right product to market, at the right time, and for the right price, but that those principles translated into practices create a healthy, productive, and adaptive work environment that none of the prepackaged methodologies can ever hope to touch.

My devotion to Agile principles and practices, those rules of the game, is therefore not based on a pedantic need to follow some arbitrary formula. Once a team I am coaching learns how to play at a basic level, which typically happens very quickly, I help them learn how to adapt their practices as needed, all the while keeping the principles in the forefront of everyone's mind. We're just not going to start there, on the highly adaptive end of the time line.

So yes, I admit it: I am an Agile Purist.

All for now....

...-.-

Is it a Group or a Team?

This question often occurs to me when I'm on training or coaching assignments. The provocation is usually a statement similar to the following: "We have a development team of 250 highly skilled engineers...." or "Our QA team just can't seem to keep up with development...." or "The business analysis team writes all of our requirements...." or "Our middleware team serves multiple simultaneous projects."

It is common usage to apply the term "team" to mean any collection of individuals who perform some related function, regardless of how those individuals actually work. To me, a team is a very specific type of human organizational unit, defined by how it works, rather than by what it works on. Simply put, teams are distinguished by teamwork. I have even, very occasionally, encountered fair approximations of cross-functional Scrum "teams" that fail to meet this most basic definition.

Teamwork describes a particular way of working toward a shared goal. I have distilled the essential characteristics of teamwork into the following (incomplete) list:

Implied in my list of teamwork traits is a self-organizing, empowered team that has the authority to set its own commitments and determine how best to meet those commitments. Another implication is that a team is small. The standard Scrum guideline for team size (seven plus/minus two) has always worked brilliantly in my coaching experience.

So the next time you hear a client or colleague talking about a "team," make sure you know what they really mean: Is it a Team or a Group?

All for now....

...-.-

It is common usage to apply the term "team" to mean any collection of individuals who perform some related function, regardless of how those individuals actually work. To me, a team is a very specific type of human organizational unit, defined by how it works, rather than by what it works on. Simply put, teams are distinguished by teamwork. I have even, very occasionally, encountered fair approximations of cross-functional Scrum "teams" that fail to meet this most basic definition.

Teamwork describes a particular way of working toward a shared goal. I have distilled the essential characteristics of teamwork into the following (incomplete) list:

- sublimation of individual ego and need for recognition to the needs of the team

- sharing and balancing workload dynamically at daily or finer granularity

- individuals offering and requesting help in an environment of trust

- willingness to make personal sacrifices in support of the team

- recognition that the team's goal outweighs (but does not exclude) individual goals

Implied in my list of teamwork traits is a self-organizing, empowered team that has the authority to set its own commitments and determine how best to meet those commitments. Another implication is that a team is small. The standard Scrum guideline for team size (seven plus/minus two) has always worked brilliantly in my coaching experience.

So the next time you hear a client or colleague talking about a "team," make sure you know what they really mean: Is it a Team or a Group?

All for now....

...-.-

Tuesday, April 6, 2010

The Law of Unintended Consequences

This is big topic, but today I want to talk about just one small aspect: the unintended consequence of command-and-control work environments. There is a persistent myth in the software business that runs something like this: if we plan every detail of our product, assign the details to individuals, monitor and track each individual's progress on each task, make sure the load is balanced across individuals and always at the maximum (or just a little more) that each individual can deliver, and if we put in place sufficient incentives and penalties to make sure that individuals follow the plan exactly, the end result will be a perfectly executed project.

Aside from the obvious difficulties of planning a future over which we mere mortals have neither control nor even foreknowledge, there is a massive gotcha lurking in the shadows of this defined, command-and-control approach that is the result of the Law of Unintended Consequences: malicious obedience.

Malicious obedience is a common behavioral response to situations in which individuals know that they have no control over what they work on, how they work, or the outcome they produce. When the incentive/penalty structure emphasizes obedience over all else, people learn very quickly to do precisely what they are told and nothing more, even if they know perfectly well that what they are doing is not the best way to achieve the end goal, which in the software industry is a working, valuable product. A common example, and one that I have experienced on more than one occasion, is when developers write code exactly as specified even when they know that what they're coding is incompatible with some other part of the system, either because of an initial design failure or a requirements change that did not propagate to their part of the system in time. Since command-and-control values obedience over all else, the developers in question had no choice but to follow the plan, write the code as specified, generate waste, and damage the overall project. "We were just following orders, sir."

Since a successful project is (or should be) the actual goal, the cure is to apply Agile principles and practices throughout. When people choose their own daily tasks, freely commit as members of a team to deliver a Sprint backlog, and have control over how they implement a solution, malicious obedience is no longer an issue. To put it another way, removing the compulsion to follow arbitrary orders from the equation eliminates the possibility of malicious obedience. When people are empowered to take ownership of their work, the Law of Unintended Consequences breaks down, resulting in innovative solutions, sterling quality, and timely feature delivery.

All for now....

...-.-

Aside from the obvious difficulties of planning a future over which we mere mortals have neither control nor even foreknowledge, there is a massive gotcha lurking in the shadows of this defined, command-and-control approach that is the result of the Law of Unintended Consequences: malicious obedience.

Malicious obedience is a common behavioral response to situations in which individuals know that they have no control over what they work on, how they work, or the outcome they produce. When the incentive/penalty structure emphasizes obedience over all else, people learn very quickly to do precisely what they are told and nothing more, even if they know perfectly well that what they are doing is not the best way to achieve the end goal, which in the software industry is a working, valuable product. A common example, and one that I have experienced on more than one occasion, is when developers write code exactly as specified even when they know that what they're coding is incompatible with some other part of the system, either because of an initial design failure or a requirements change that did not propagate to their part of the system in time. Since command-and-control values obedience over all else, the developers in question had no choice but to follow the plan, write the code as specified, generate waste, and damage the overall project. "We were just following orders, sir."

Since a successful project is (or should be) the actual goal, the cure is to apply Agile principles and practices throughout. When people choose their own daily tasks, freely commit as members of a team to deliver a Sprint backlog, and have control over how they implement a solution, malicious obedience is no longer an issue. To put it another way, removing the compulsion to follow arbitrary orders from the equation eliminates the possibility of malicious obedience. When people are empowered to take ownership of their work, the Law of Unintended Consequences breaks down, resulting in innovative solutions, sterling quality, and timely feature delivery.

All for now....

...-.-

Tuesday, March 16, 2010

The Ghost of Frederick Winslow Taylor, Part 4

Last time we saw the Utopian glimmer Taylor thought his vision of scientific management offered. Let's wrap that up and get to the Agile connection this time.

In his cold, raspy, ethereal voice, Taylor's ghost asserts that scientific management gives both workers and management what both groups most want, viz., high wages and low per-piece labor costs (cf. p 93). He goes on to say that workers "should" be encouraged and allowed to propose new and better methods of working, which after adequate study and experimentation, management may choose to adopt as the new standard for a given task. The individual worker who proposed the new method "should" receive full credit for the innovation and be paid a cash bonus as a reward (cf. p. 128). Taylor is unable to provide an answer to the question of just how exactly any worker, bound up by the rigid work rules and defined pace scientific management imposes, could ever have the opportunity even to think of a better way of performing a work task. Even worse, management is under no obligation to allow workers to experiment with alternative ways of working.

Taylor wraps up his case with yet another Utopian flourish. First, he states that the new division of duties between labor and management along with "intimate, friendly cooperation" ensures labor peace (cf. p. 140). And finally, scientific management, by dramatically increasing wages ends the wage problem. Even more, the close, constant, and intimate cooperation (there's that formula yet again) between management and labor produces a commonality of interest that makes labor strife impossible. The broader benefits that result are reduction in poverty (through high wages), cheaper products, and better competitiveness even during economic downturns, resulting in minimal economic dislocation (cf. pp. 143-44).

Those are bold statements, but they are -- and always were -- as ethereal as the ghost who continues to assert their validity. First off, Taylor never had any evidence to support his Utopian vision of labor-management cooperation and perpetual peace. Labor strife did not end as scientific management spread. Indeed, scientific management simply escalated the labor-management war by giving management a potent weapon to use against labor. Secondly, he simply ignored the greed and lust for power that characterize the owners and managers of capitalist enterprises. Scientific management came into widespread use and indeed is still at least implicit in the vast majority of businesses of all types.

Taylor provided the theoretical basis for management to remove every shred of the workers' control over the work they were doing. He took away their tools, their knowledge and expertise, and their genius for self-organization and replaced them with rigid command-and-control structures that governed every aspect of work. His predictions of huge increases in productivity, the one aspect of scientific management for which he had good data, were indeed realized. High wages did not follow, however. Industrial management realized that they could realize vastly higher profits by reducing their workforces by the 80-90% Taylor forecast. As scientific management spread rapidly throughout the US economy, high unemployment became the norm, making it very easy for management to use scientific management to squeeze high productivity from workers while offering only the threat of replacement as an incentive to stay in their increasingly oppressive jobs. Henry Ford's famous doubling of his workers' wages in 1914 was short-lived: a stockholder rebellion and resulting lawsuit forced wages back down.

So where's the long-awaited Agile connection, you might ask (I'm sure you are)? Easy. Taylor was wrong. Scientific management, with its heavy handed, command-and-control work methods, stifled innovation by making it impossible for the people actually doing the work to contribute to the development of new and better products. Agile frees this most important source of innovative thinking from the bonds of rigid work rules and suffocating management oversight. Companies haunted by the ghost of Frederick Winslow Taylor stagnate and are unable to adapt to the rapidly changing economic conditions that are now the rule rather than the exception.

Chase Taylor's ghost from your building -- and from your mind. Take advantage of the power of self-organization. Win in the market by being adaptable, by drawing upon the power of innovation that comes with building teams of motivated individuals and trusting them to get the job done. It's long past time for Taylor's ghost and his century old prescriptions to be laid to rest.

All for now....

...-.-

References

Taylor, Frederick Winslow, The Principles of Scientific Management. New York & London: Harper, 1911, reprint edition, 1934.

Monday, March 8, 2010

The Ghost of Frederick Winslow Taylor, Part 3

Since scientific management requires companies to define each task to the finest detail, there must be a massive expansion of management activity going on as well. And indeed, that is the case. According to Taylor, scientific management requires the establishment of a large and elaborate management structure to plan the work of each worker at least a day in advance, record each worker’s output, train each worker as needed for each task, keep and issue necessary tools each day, etc (cf. p. 70). Whereas previously, workers had provided their own tools, expertise, and initiative, now all three of those categories would fall strictly under the control of the new, massively expanded management.

Achieving maximum output requires cooperation, but no individual worker has the authority to require peers to cooperate in that effort. Only management has that power. Therefore,

“It is only through enforced standardization of methods, enforced adoption of the best implements and working conditions, and enforced cooperation that this faster work can be assured. And the duty of enforcing the adoption of standards and of enforcing this cooperation rests with the management alone.” (cf. p. 83. Original emphasis)

Management must train all workers and dismiss those who are unable to meet the required work pace after training. Management must also recognize that workers will not submit to rigid task standardization and faster pace of work unless they receive a substantial increase in pay in return. And finally, all four components of scientific management must be applied in order to realize the promised results (see the previous post in this series).

This is beginning to sound less and less Utopian, despite Taylor's repeated and plaintive calls for dramatic wage increases after the adoption of scientific management.

Next time we'll drive a stake through the heart of Taylor's Utopian daydream and examine the consequences of his ideas.

All for now....

...-.-

References

Taylor, Frederick Winslow, The Principles of Scientific Management. New York & London: Harper, 1911, reprint edition, 1934.

Friday, March 5, 2010

The Ghost of Frederick Winslow Taylor, Part 2

The new role of management under scientific management is to provide task-level standardization of methods to achieve maximum efficiency from each worker. In return for vastly increased productivity, workers must receive 30-100% increase in wages or else they will simply not agree to work in a new way. With management taking on half the burden of the work, in the form of task-level planning, and the increase in pay, labor-management relations will be automatically close and cordial (cf. p. 27).

Taylor's thesis was that only through scientific management could both employer and worker fulfill their needs and ambitions and that once those criteria were met, there would no longer be any cause for labor unrest. The backdrop to Taylor's work was the intense, violent, and often bloody warfare then taking place between owners and workers, both in the US and in Europe. There was also the ideological struggle being waged between industrial capitalism, socialism/communism, and anarchism. Taylor attempted to demonstrate that by cooperating in a spirit of shared sacrifice, labor and management could work together for the benefit of everyone. We'll assess the success of his prescriptions in that area later as well. Suffice it to say that following a visit by Taylor to a workplace, 80%-90% of the original workforce joined the ranks of the unemployed. But back to our Taylor haunting....

Taylor urged management to take on the responsibility of collecting all of the tacit knowledge of every trade practiced in their enterprise and “classifying, tabulating, and reducing this knowledge to rules, laws, and formulae which are immensely helpful to the workmen in doing their daily work.” Management would also take on four essential tasks that form the heart of scientific management:

- Develop the science for each element of the work every worker performs, using time and motion studies, etc.

- Scientifically select, train, teach, and develop each worker to the highest level. Previously workers chose their own work and carried out their own training by whatever means they could arrange.

- Management must “heartily cooperate with the men so as to insure all of the work [is] being done in accordance with the principles of the science which has been developed.” This means training at the task level.

- Almost equal division of work and responsibility between management and labor, with management taking on the science and task-level direction of each worker (cf. pp. 36-37).

So where are we at? So far we have vastly improved productivity, a recommendation for much higher wages, labor-management cooperation, task-level direction, and extreme and increasing division of labor. That is at best a mixed ledger. Next time, we'll look at Taylor's ideas on cooperation and how it is to be achieved. We'll also begin to form a picture of what scientific management meant to the people doing the work. And don't worry -- we'll get to the Agile connection very soon.

All for now....

...-.-

References

Taylor, Frederick Winslow, The Principles of Scientific Management. New York & London: Harper, 1911, reprint edition, 1934.

Wednesday, February 24, 2010

The Ghost of Frederick Winslow Taylor, Part 1

How could one dead white guy have that much influence, you might ask? The answer lies in a paper Taylor presented to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) in 1911 and later published as a short book. Both presentation and book bore the title: The Principles of Scientific Management.

Taylor's purpose was to explore President Theodore Roosevelt's call to increase national efficiency and was a part of the larger efficiency craze sweeping the United States in the early twentieth century. William Howard Taft was president of the US in 1911, when Taylor presented his findings and prescription for industrial efficiency, but no matter.

Taylor set out to use the scientific method (or just "science!" as Thomas Dolby sang back in the 1980's) to secure maximum prosperity for both employer and employees by developing each employee to a state of maximum efficiency in the highest grade of work for which each employee was suited. Taylor was speaking of manual labor, both skilled and unskilled, of course, since there was no such thing as a "knowledge worker" in that day and age.

Taylor's observations of working people led him to the conclusion that any "work gang" left to its own devices would work only at the level of its least efficient member. In those days, the term for slowing work to that level was "soldiering." Taylor understood that the workers engaged in soldiering to protect their own interests against what he called "defective management practices." Workers believed, and as it turned out rightfully so, that broad increases in productivity would lead to mass unemployment, then as now, the scourge of the American economy. More on that in a later installment.

Taylor identified the key elements of labor inefficiency:

- Workers use rule-of-thumb practices handed down through observation of their peers. There were no standardized practices even within the same trade within the same company. Management does not know how the work is done and therefore leaves the heavy responsibility for figuring out how to do the work up to the workers themselves.

- The worker best suited for a particular job is incapable of understanding the scientific laws governing the most efficient way to complete the work. Taylor stated that it was the duty of management to take on half the workload by deriving those very scientific laws and then providing the resulting information and training to the workers.

More on Taylor's ideas next time.

All for now....

..-.-

References

Taylor, Frederick Winslow, The Principles of Scientific Management. New York & London: Harper, 1911, reprint edition, 1934.

Pragmatism

Pragmatism is a word I hear quite often in my coaching life. Webster's defines pragmatism as "a practical approach to problems and affairs." To me, that is also the definition of Agile. Every minute of training or coaching I deliver is devoted to building a practical approach to whatever problems the client is facing. With its focus on flexible planning based on realistic time horizons, short-term commitments, frequent deliveries and adjustments, Agile is the acme of pragmatism.

Where I find the term pragmatism problematic is when clients or colleagues use it as an excuse to paper over or otherwise avoid addressing issues that Agile principles and practices expose. Overcoming impediments is a part of the Agile game and the only path to continuous improvement, so declaring that some set of organizational or corporate-cultural impediments cannot be overcome is simple capitulation, not pragmatism.

That is not to say, of course, that it is possible or even desirable to change everything about an organization overnight. Successful Agile coaches -- and successful Agile clients -- are committed to playing by the rules of the game, even if getting there is a process of incremental change rather than a single, sweeping event.

The vital thing to keep in mind is that Agile, whether XP, Scrum, Lean, etc., or some combination, is a framework, something like a scaffold, in which every key aspect depends on other key aspects. What this means in practice is that for companies to be successful with Agile, they -- and their Agile coaches -- cannot pick and choose amongst the principles and key practices, deciding to implement some and ignoring those that are difficult or otherwise inconvenient. As Takeuchi and Nonaka* put it so succinctly 25 years ago when they wrote about a new way of developing products: "These characteristics are like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Each element, by itself, does not bring about speed and flexibility. But taken as a whole, the characteristics can produce a powerful new set of dynamics that will make a difference."

Agile today is no different than the "new new product development game" Takeuchi and Nonaka described in their ground-breaking article. Pragmatism does not mean dropping the troublesome pieces of the puzzle on the floor; it means finding practical ways to implement the key practices and all Agile principles in a given context. And that is "a practical approach to problems and affairs."

All for now....

...-.-

*Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ikujiro Nonaka. "The New New Product Development Game." Harvard Business Review, January 1986, p. 138.

Where I find the term pragmatism problematic is when clients or colleagues use it as an excuse to paper over or otherwise avoid addressing issues that Agile principles and practices expose. Overcoming impediments is a part of the Agile game and the only path to continuous improvement, so declaring that some set of organizational or corporate-cultural impediments cannot be overcome is simple capitulation, not pragmatism.

That is not to say, of course, that it is possible or even desirable to change everything about an organization overnight. Successful Agile coaches -- and successful Agile clients -- are committed to playing by the rules of the game, even if getting there is a process of incremental change rather than a single, sweeping event.

The vital thing to keep in mind is that Agile, whether XP, Scrum, Lean, etc., or some combination, is a framework, something like a scaffold, in which every key aspect depends on other key aspects. What this means in practice is that for companies to be successful with Agile, they -- and their Agile coaches -- cannot pick and choose amongst the principles and key practices, deciding to implement some and ignoring those that are difficult or otherwise inconvenient. As Takeuchi and Nonaka* put it so succinctly 25 years ago when they wrote about a new way of developing products: "These characteristics are like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Each element, by itself, does not bring about speed and flexibility. But taken as a whole, the characteristics can produce a powerful new set of dynamics that will make a difference."

Agile today is no different than the "new new product development game" Takeuchi and Nonaka described in their ground-breaking article. Pragmatism does not mean dropping the troublesome pieces of the puzzle on the floor; it means finding practical ways to implement the key practices and all Agile principles in a given context. And that is "a practical approach to problems and affairs."

All for now....

...-.-

*Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ikujiro Nonaka. "The New New Product Development Game." Harvard Business Review, January 1986, p. 138.

Friday, February 19, 2010

The Meaning of Commitment

A common dysfunction I encounter when coaching Agile teams is a failure to understand the meaning of commitment. Scrum teams commit to delivering the Sprint backlog -- complete, tested, and ready to be shown to stakeholders by the end of the Sprint. That commitment means that the team members agree, freely and entirely of their own volition, to do their level best to meet their collective Sprint commitment. Does it always work out exactly as planned? No, of course not. But over the course of repeated Sprints, teams learn what that commitment looks and feels like and they get better at delivering on their commitments.

The lament I frequently hear is: "This team always misses its commitments." Oddly enough, I almost never hear that from members of the team in question. The source of the complaint is almost always from a stakeholder, functional manager, or executive at some level.

In the rare instance of a team whose members acknowledge that they routinely fail to meet their commitments, I work with the ScrumMaster, Product Owner, and team to ensure that they have good stories, solid acceptance criteria, follow the Agile rules for estimating, and that they understand the importance of building trust by doing what you say you are going to do. A team-based commitment failure is usually not difficult to overcome, although sometimes there can be a painful drop-off in perceived productivity as the team learns how to make a realistic commitment and deliver on it.

The much more common case of a stakeholder, functional manager, or executive expressing exasperation with routine commitment failure is usually easier to diagnose, but often more difficult to cure. The essential problem is a failure to understand that the team itself must commit to the Sprint backlog, freely and with complete consensus among team members. Any hint of a commitment that is forced from outside or arrived at without team consensus is automatically invalidated.

Think for a moment about the nature of commitment. We make commitments at many points in our lives. Marriage is a commitment. Having children and being a good parent is a commitment. While a Sprint backlog is trivial in comparison, the nature of the commitment required is exactly the same. Commitment must be voluntary. Commitments cannot be taken lightly. Commitment is a personal decision, sometimes taken in a collective context, as with a Sprint commitment when a team arrives at consensus.

One recent example of habitual commitment failure demonstrates very clearly a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of commitment and the inevitable result. On a coaching engagement, I heard from an executive that several teams never met their Sprint commitments. He was intensely frustrated with the situation. A little probing of the situation revealed the exact nature of the problem: When asked where the Sprint commitment for the teams in question came from, his response was, "I tell them what they'll commit to each Sprint." It turns out that he had laid out the teams' Sprint commitments months in advance. I explained that a Sprint commitment forced on a team from outside placed the team under no obligation whatever and that such a policy had completely undermined the company's entire Agile practice. When the members of the teams confirmed my assessment of the situation, the executive backed off and started allowing each team to make and deliver its own Sprint commitments. The problem of Sprint commitments not delivered vanished instantly.

A related problem at the same client proved to be the result of the ScrumMaster assigning all tasks at Sprint planning. The team did have control over its Sprint backlog commitment, but pre-assigning tasks left the team fragmented, demoralized, and unable to make the daily adjustments necessary to meet their commitment. When the ScrumMaster agreed to allow team members to self-assign tasks on a daily basis and to self-organize, using the daily Scrum, to ensure that they did everything possible to meet their Sprint commitment, the result was amazing. The team became cohesive, lively, and productive. They began meeting their Sprint commitments and experienced a remarkable increase in velocity after a few Sprints.

Commitment is not just a buzz-word. It is a vital component of Agile and a key ingredient in every team's success. So do the right thing, empower your teams to commit and reap the benefits.

All for now....

...-.-

The lament I frequently hear is: "This team always misses its commitments." Oddly enough, I almost never hear that from members of the team in question. The source of the complaint is almost always from a stakeholder, functional manager, or executive at some level.

In the rare instance of a team whose members acknowledge that they routinely fail to meet their commitments, I work with the ScrumMaster, Product Owner, and team to ensure that they have good stories, solid acceptance criteria, follow the Agile rules for estimating, and that they understand the importance of building trust by doing what you say you are going to do. A team-based commitment failure is usually not difficult to overcome, although sometimes there can be a painful drop-off in perceived productivity as the team learns how to make a realistic commitment and deliver on it.

The much more common case of a stakeholder, functional manager, or executive expressing exasperation with routine commitment failure is usually easier to diagnose, but often more difficult to cure. The essential problem is a failure to understand that the team itself must commit to the Sprint backlog, freely and with complete consensus among team members. Any hint of a commitment that is forced from outside or arrived at without team consensus is automatically invalidated.

Think for a moment about the nature of commitment. We make commitments at many points in our lives. Marriage is a commitment. Having children and being a good parent is a commitment. While a Sprint backlog is trivial in comparison, the nature of the commitment required is exactly the same. Commitment must be voluntary. Commitments cannot be taken lightly. Commitment is a personal decision, sometimes taken in a collective context, as with a Sprint commitment when a team arrives at consensus.

One recent example of habitual commitment failure demonstrates very clearly a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of commitment and the inevitable result. On a coaching engagement, I heard from an executive that several teams never met their Sprint commitments. He was intensely frustrated with the situation. A little probing of the situation revealed the exact nature of the problem: When asked where the Sprint commitment for the teams in question came from, his response was, "I tell them what they'll commit to each Sprint." It turns out that he had laid out the teams' Sprint commitments months in advance. I explained that a Sprint commitment forced on a team from outside placed the team under no obligation whatever and that such a policy had completely undermined the company's entire Agile practice. When the members of the teams confirmed my assessment of the situation, the executive backed off and started allowing each team to make and deliver its own Sprint commitments. The problem of Sprint commitments not delivered vanished instantly.

A related problem at the same client proved to be the result of the ScrumMaster assigning all tasks at Sprint planning. The team did have control over its Sprint backlog commitment, but pre-assigning tasks left the team fragmented, demoralized, and unable to make the daily adjustments necessary to meet their commitment. When the ScrumMaster agreed to allow team members to self-assign tasks on a daily basis and to self-organize, using the daily Scrum, to ensure that they did everything possible to meet their Sprint commitment, the result was amazing. The team became cohesive, lively, and productive. They began meeting their Sprint commitments and experienced a remarkable increase in velocity after a few Sprints.

Commitment is not just a buzz-word. It is a vital component of Agile and a key ingredient in every team's success. So do the right thing, empower your teams to commit and reap the benefits.

All for now....

...-.-

Sunday, January 24, 2010

Some Musings on Recognition

Watching the Golden Globe awards the other night, a couple of things struck me. The first was that people who do excellent work were being recognized for it. The reason that struck me is that, in my personal and consulting experience during the last decade, I have seen essentially nothing resembling a corporate award program for excellence in the workplace in the United States. I'm sure there are companies that still engage in this now seemingly quaint activity, but such things are not the norm anymore.

So what's up with that? Are we so deeply buried in the "just be happy you have a job" mentality that we have no time or interest to promote and reward excellence in the workplace? Perhaps this is a symptom of the pervasive job dissatisfaction plaguing the US. Currently 55% of Americans are dissatisfied with their jobs. I'm not sure where the answer lies. What I do know is that we cannot afford to have a largely disaffected workforce if we in the US intend to avoid a sharp and disastrous economic decline.

The other thing that struck me about the awards show was that, as each winner spoke about the privilege of receiving the award, thanking parents, spouses, children, directors, actors, the Hollywood Foreign Press Association, etc., they all kept coming back to the statement that their project was a collaborative endeavor involving a team of dedicated professionals. Martin Scorsese hit on this point repeatedly in his speech.

So what does any of this have to do with coaching Agile teams? The first thought I have is that there is nothing inimical to teamwork in recognizing individual contributions to the success of the team. We don't want to encourage the development of a hero mentality within a team or destructive internal competition, but it is entirely appropriate to recognize individual excellence in a team setting.

How do we recognize excellence in a way that promotes teamwork? One excellent way is to include appreciations in every team retrospective. Not only do appreciations help build a team mentality, they also provide an incredibly appropriate setting in which to recognize individual excellence in a team setting.

All for now....

...-.-